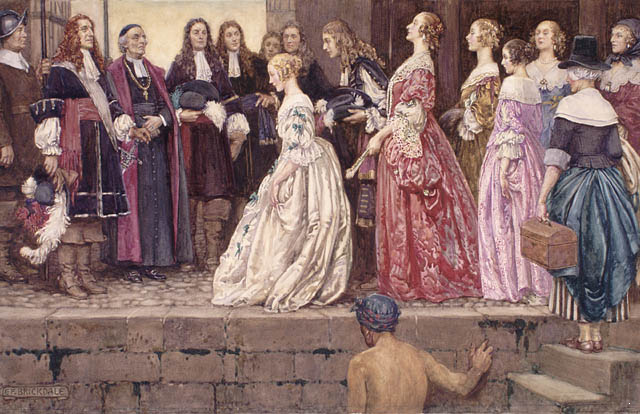

Les filles du roi

“Les filles du roi, Québec” by Brickdale (courtesy of the National Archives of Canada)

Our ancestor Mathurine Graton is considered to be a fille du roi, or King’s Daughter, having arrived in New France in 1670 as a single woman of 18 or 22 years of age. The term “Fille du roi” is first seen in the writings of Marguerite Bourgeoys in around 1697-1698. It was not repeated until historian Étienne-Michel Faillon used it in 1853. According to historian and demographer Yves Landry (in his book “Les Filles du roi au xvii’ème siècle”), the term derives from “enfants du roi” (children of the King), which was used in 17th century Canada to refer to children without parents (orphans) who were raised at the King’s expense.

What is a “Fille du roi”?

Although there were several definitions of the term throughout the 20th century, the currently accepted meaning of fille du roi is a marriageable woman, single or widowed (including widows with children), who arrived in Canada between 1663 and 1673 inclusive, and who is presumed to have benefited from royal aid in her transport to and/or settlement in New France. King Louis XIV, through his Minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, instituted a program to settle marriageable women in New France in order to support the creation of families and increase the population of the struggling colony. Canada had a population of a mere 3200 in 1663.

This effort was commenced in 1663 and lasted until 1673, and was coupled with sending the first regular French army regiment, the Carignan-Salières Regiment, to New France in 1665 to put a stop to the Mohawk raids on the colony’s settlements.

See a list of all the Filles du roi at the following link on the website of La Société des Filles du roi et soldats du Carignan: https://fillesduroi.org/cpage.php?pt=9.

As a result, at least 770 women arrived in New France as Filles du roi in that 11 year period: 737 of the Filles du roi settled in Canada; and 33 others arrived there, but either returned to France, died, or remained without marrying. According to Mr. Landry’s research, some of these women were recruited and transported at the King’s expense; others came to the ports of La Rochelle or Dieppe on their own, and were integrated into the group; and again others were neither recruited nor transported by the King, but arrived between 1663-1673 and their settlement was facilitated by colonial administrators (less than 100, mostly during 1664, 1666 and 1672).

The number of arrivals of Filles du roi according to Landry’s research are as follows: 1663: 36; 1664: 15; 1665: 90; 1666: 25; 1667: 90; 1668: 81; 1669: 132; 1670: 120; 1671: 115; 1672: 15; and 1673: 51. Almost one half of the Filles du roi arrived during 1669 to 1671. This follows the demobilization and settlement of over 400 of the Carignan-Salières Regiment’s soldiers and officers in Canada in 1668. Previously, between 1634 and 1662, while the colony was governed by the private Compagnie des Cents Associés, only about 220 filles à marier were brought to the colony.

Backgrounds of the Filles du roi

The King’s Daughters were of diverse cultural backgrounds, but nearly 80% were from either Paris, Normandy or the West of France. Almost 50% came from around Paris (Ile de France); most of those arrived in New France in 1665, 1669, 1670 or 1671. Only 6% were from countries other then France, and only 2% were Protestant (despite the 123 departures of Filles du roi [out of 770] from the port of La Rochelle, a protestant stronghold).

Two-thirds of the King’s Daughters were of urban versus rural origins, though only 15% of the population of France at the time lived in cities, as noted by Mr. Landry. One half of the urban King’s Daughters were from Paris. These numbers can be compared to the two-thirds of male settlers of known origin in Canada at that time who arrived before 1680 and were from rural areas.

Two women in particular, Mme. Bourdon and Mme. Estienne, acted as recruiters of women as Filles du roi, concentrating on the Hôpital général de Paris during the 1669-1671 migrations. The very great majority of the King’s Daughters were from extreme poverty. It’s likely they left France because of financial difficulties, whether they were orphans from the Hôpital général de Paris or their parents sent them off.

Landry’s findings assume that 58% of King’s Daughters would have spoken Central French (from the Ile de France); only 26% spoke semi-patois, and 16% only patois. Compare this to the distribution among the general population of France: one-fifth; one-fifth; and three fifths, respectively.

Given the high marriage and birth rate, and the traditional role of the mother in raising and educating the children, Landry concludes that the King’s Daughters could have contributed to the acceleration of the assimilation, making Central French the common speech of Canada.

Four socio-economic groups of origin (based on the father’s profession) were represented among the Filles du roi: nobility & bourgeoisie; tradesmen; farmers; and the “humble” occupations. Landry estimates that only 12% of the King’s Daughters fell into the first group, contrary to earlier writings. This figure is comparable to the percentage in the general population of France, and slightly less than that in the population of Canada at the time.

Landry describes how the general lack of money and personal goods among Filles du roi demonstrates the importance played by the royal aid in their settlement. Royal aid consisted of the cost of the voyage, assistance upon arrival, and/or a royal dowry on marriage.

Marriages

250 of the 606 known marriage contracts (or 41%) of the King’s Daughters mention a royal dowry. Almost all of them were in the sum of 50 livres, and two were 200 livres. About three-quarters of King’s Daughters of known upper socio-economic origins received only a 50 livres dowry, paid in goods. Of the seven higher dowries (100 livres or more), six were given to “demoiselles” (higher social origins). Most dowries were granted between 1669 and 1671 (244 of the 250), years when recruits of Mme. Bourdon and Mme. Estienne arrived from the Hôpital général de Paris, an orphanage.

Women who arrived with fewer possessions were more likely to receive a royal dowry at marriage. However, social class or origin did not determine the likelihood of a dowry. According to Landry, Jean Talon, the Intendant of the colony since 1665, seemed to equalize the level of wealth among the newlyweds through this practice.

The average age of single Filles du roi on arrival in Canada was 23.9 years; for widows, it was 32.5 years. Only half of these women were between 18 and 25 at immigration. However, 96% of the Filles du roi were between 16 and 40 upon settlement in New France. A total of 718 of the Filles du roi were single on arrival; 38 were widows (though Landry believes that many failed to declare their true status for fear of rejection); and 14 were of unknown status. Only 24% could sign their name, a rough estimation of literacy.

Landry found that 56.7% (387 of 663) of Filles du roi who provided information had a deceased father upon immigration; 19% had a deceased mother; and 11.3% were complete orphans. Mathurine Graton was in the latter category. Thus 64.4% of the Filles du roi (who provided the information) were orphaned of at least one parent. This percentage was even higher among women recruited by Mmes. Bourdon and Estiennes from Paris in 1669-1671.

Landry points out that some Filles du roi may have been incited to immigrate by family ties to other immigrants who preceded, accompanied or followed them to Canada. Certainly this was the case of Mathurine Graton, who travelled to New France either together with or during the same summer as her brother and his family. One in ten King’s Daughters were related to someone in New France; however, this percentage was low compared to the general French immigrant population, among whom two in three were related to a Canadian (pre-1700).

738 of the Filles du roi known to arrive in New France married at least once in the colony; 181 married twice; 35 married three times; and two married four times. Landry reports that marriageable men outnumbered available women between six and fourteen times in Canada up to 1670; whereas, by 1679, this ratio had decreased to two to one. The average interval between arrival and first marriage in the 1663-1673 period was 4.7 months. From year to year, the average varied from one month (1673) to 8.5 months (1667).

Settlement

The Filles du roi resided initially at reception centers in Quebec City, at the Hôtel Dieu hospital, and at houses of the Ursuline nuns and of individuals such as Mme. La Peltrie and Anne Gasnier, following their arrival in the colony. In Montreal, some resided at the Maison Saint-Gabriel, which currently is open as a museum.

The King’s Daughters dispersed throughout the colony after marriage, with few (10%) settling where they had just married in Quebec City. More than half of the couples settled in a different parish within a radius of 40 km or more from Quebec City, including the Ile d’Orléans. The areas around Montreal and Trois-Rivières attracted 26% and 12% of the newlyweds, respectively. But only 16% of the Filles du roi founded their new homes in the major towns of the colony.

The first official act in the nuptial process for the Filles du roi was an oral promise of marriage called a declaration of “fiançailles” (fiancees). Next came the marriage contract. Though not a necessity, 82% of the Filles du roi entered into one with their husbands for their first marriages (most did so prior to the religious ceremony), as opposed to only 65% of couples during the earlier 1632-1662 period.

Not all contemplated marriages took place. Fifteen percent of the King’s Daughters who signed first marriage contracts did not marry their intended (highest during 1669-1671), resulting in annulment of the contract. According to Landry, this was three times the rate of annulments for the period 1632-1662 and twice as high as for second marriages for the Filles du roi. And another 13% of these women did not marry following a second try at a first marriage.

Most of the husbands in the first marriages of the Filles du roi were born in France (95%). Only 3% were Canadian-born; but then, only 10% of the males in the colony were born there, notes Landry. Yet there was a high degree of cultural mixing in the choice of spouses. For example, whereas half of the wives were from the region around Paris, only 8% of the husbands hailed from that area (among persons of known origin). Only 18.7% of spouses were from the same region, as compared to a rate of 33% among Canadian couples generally before 1680.

Children of the Filles du roi

Landry found that 71% of the children born to the King’s Daughters entered the world between 1670 and 1685. In all, there were a total of 4459 births to Filles du roi from 1664-1702. Baptismal and later records (especially the census of 1681) were used to track these births. Over 100 births per year occurred during 1669-1687 alone. One-third of the first-borns of the Filles du roi were conceived during the period of November through January; in other words, within a very few months of the profusion of autumnal weddings that took place shortly after the summer arrivals of these women in the colony.

Landry found that a Fille du roi had on average 5.8 children during her lifetime (after statistical correction), at a time when New France was sparsely populated. The author also noted that the average Fille du roi’s marriage lasted 23.5 years. In couples who lived at least to age 45, Landry found that a Fille du roi who married between the ages of 20-24 had an average of 8.5 children, and one who married between 25-29 had an average of 5.7 children. Of course, there are always exceptions to the rule: Catherine Ducharme and her husband Pierre Roy dit Lambert beat the average; they had 18 children over their 27 year marriage! The Filles du roi gave birth to 46% of their first-born children before their first anniversary of marriage, with an average of less than 13 months between the two dates.

Lifespan

Landry calculates that the average age of a Fille du roi at death was 62.2 years. Almost two-thirds of the group died in the first 30 years of the 18th century. He determined that life expectancy for the Filles du roi at birth was 42.5 to 45 years; but that at age 20, a King’s Daughter had a life expectancy of 61.4 additional years! This was an exceptional duration of life for the 17th century.

Landry compares this statistic to known European life expectancy figures, and concludes that only women of old ruling class families in Geneva had a longer life expectancy at age 20. This rate even surpassed that of ruling classes in the rest of Europe; some did not reach this level until the late 19th century!

On average, at least one spouse had been married previously in roughly one in four marriages of the King’s Daughters, according to Landry. He shows us that the adoption of step-children was not a deterrent to remarriage in this society: 86% of widows were under 40 years old, and three-quarters of those remarried while responsible for five or more children.

Conclusion

Despite the brief 11 year period of the Filles du roi program in New France, this group of women stand out significantly as founders of the French-Canadian population, notwithstanding their origins in poverty in France and the pressure on them to marry quickly following their arrival in New France. The healthy and safer Canadian environment, combined with the hardiness of these women who had survived exposure to illness and difficult circumstances in France, the harsh voyage across the Atlantic, and the desolate Canadian landscape, led to a population boom in Canada and the survival of the colony and the French-speaking people in North America.

Researched & Written by David Toupin, great-grandson of Felix Toupin.

References

Yves Landry, Les Filles du roi au xvii’ème siècle: Orphans in France, Pioneers in Canada, 1992, Leméac

Peter J. Gagné, King’s Daughters and Founding Mothers: The Filles du Roi, 1663-1673, 2001, Quintin Publications.